Theatre, film, music, spoken word, events

-

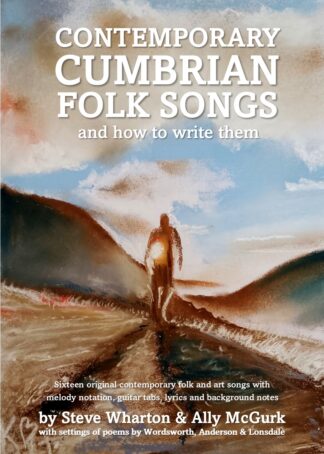

Contemporary Cumbrian Folk Songs

And How To Write Them

£12.00 -

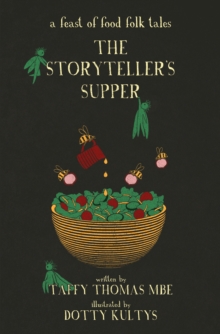

The Storyteller’s Supper

A Feast of Food Folk Tales

£12.99 -

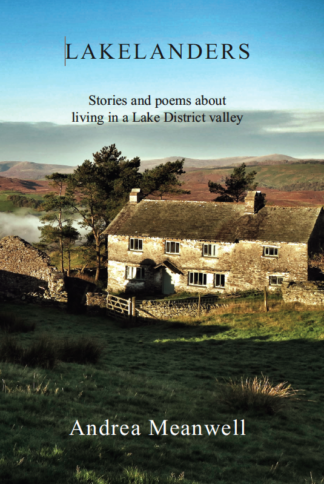

Lakelanders

Stories and poems about living in a Lake District valley

£10.00 -

The Riddle in the Tale

Riddles and Riddle Folk Tales

£9.99 -

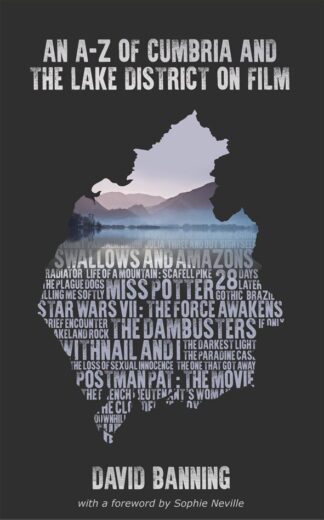

A-Z of Cumbria and the Lake District on Film

£12.00 -

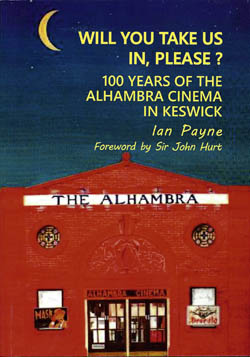

Will You Take Us In, Please?

100 Years of the Alhambra Cinema in Keswick

£10.00 -

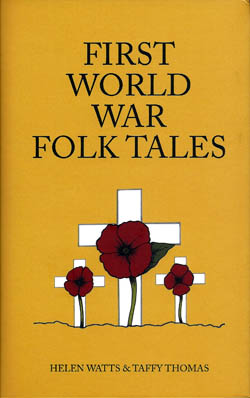

First World War Folk Tales

£9.99 -

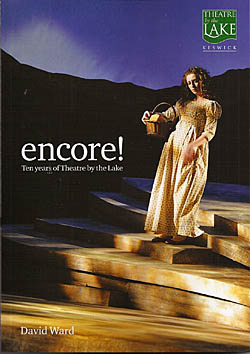

Encore!

Ten Years of Theatre By The Lake

£6.00 -

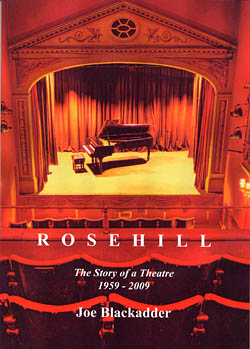

Rosehill – The Story of a Theatre 1959 – 2009

£10.00

Showing all 18 results