Cumbria has a rich cultural heritage and we highlight some of that heritage in this small selection

Art and Sculpture

(47)

Art and artists of the county

Fiction

(160)

Fiction by Cumbrian authors, and those who live in the county as well as novels set in Cumbria. Books by Melvyn Bragg and Margaret Forster (incl some non-fiction) are in separate categories.

Literary Non-Fiction

(78)

A few literary non-fiction works,on all subjects, by Cumbrian authors. All Cumbrian-based non-fiction will be found in other categories of the website

Performing Arts

(19)

Theatre, film, music, spoken word, events

Poetry

(120)

Poetry by Cumbrian poets. Wordsworth is in a separate category

-

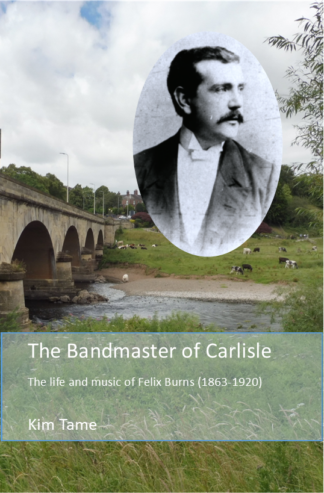

The Third Light

£16.99 -

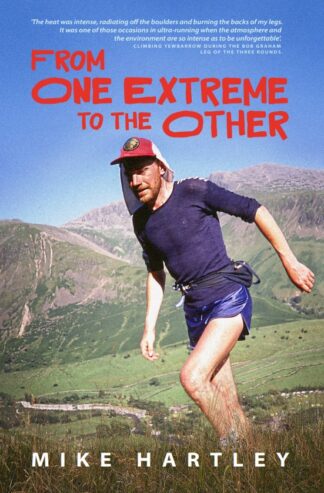

Nobody’s Hero

£16.99 -

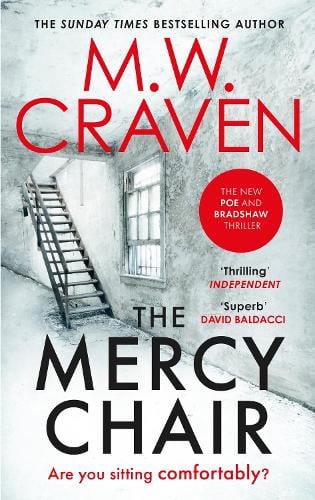

The Mercy Chair

£20.00 -

Dark Island

£9.99 -

You Are Here

£20.00 -

The Borrowed Hills

-

My Name was Eden

£16.99 -

The Restaurant At The Heart Of The Lakes

£8.99 -

A Body In The Borderlands

£9.99 -

Gwen John

A Life In Sonnets

£10.00 -

Fearless

£8.99 -

A Very Satisfactory Manner

£10.00 -

The Winter Of Our Lives

£9.99 -

A Literary Walking Tour Of Carlisle

A Countrystride Guidebook

£7.50 -

Everywhere

£5.00 -

Sketching A Year In Lakeland

£14.90 -

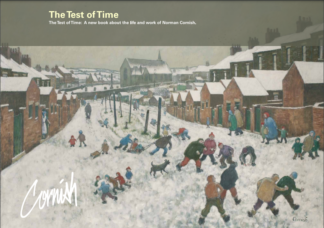

The Test Of Time

A New Book About The Life And Work Of Norman Cornish

£30.00 -

Some of us Just Fall

On Nature and Not Getting Better

£20.00

Showing 1–20 of 325 results