Cumbrian architecture, buildings and structures

-

Ring of Stone Circles

£9.99 -

The Early Medieval Monastic Site at Dacre, Cumbria

Lancaster Imprint vol 30

£22.50 -

Carlisle in 50 Buildings

£15.99 -

A New History of Penrith Book V

Penrith in the Nineteenth Century - the Victorian Town

£15.00 -

Grasmere

A History in 55 1/2 Buildings

£10.00 -

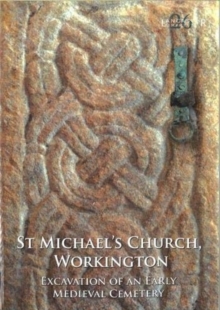

St Michael’s Church, Workington

Excavation of an Early Medieval Cemetery

£20.00 -

The Medieval Misericords in Carlisle Cathedral

£6.00 -

Churches of the Ancient Parish of Crosthwaite

£8.00 -

Barrow-in-Furness in 50 Buildings

£14.99 -

The Yards of Kendal

£14.99 -

A New History of Penrith Book II

Penrith under the Tudors

£12.00 -

Water-Power Mills of South Lakeland

£24.00

Showing 1–20 of 43 results